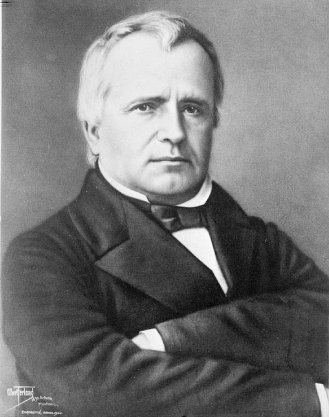

The Address to the Electors of Terrebonne

by Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine

To the electors of the county of Terrebonne,

Sirs,

The union has at last been decreed! In the thoughts of English Parliament, Canada should in the future form just one province. Is this grand political measure in the best interest of the population who'll now have to submit to one and only Legislature? We'll have to let time decide. History will say that force was imposed on the two peoples of Lower and Upper Canada. To render this measure legitimate, it requires the consent and approval of these same two peoples. While their voice can only be heard in the assembly chamber however, an act of the Imperial Parliament, with it numerous injustices, would only let a part of their legitimate representatives take their place in the first session of the new Legislature.

The exercise of arbitrary powers given to the governor in charge can postpone a general election, while it can equally bring you to the hustings 1 in a sudden and unexpected manner. Wether this time be far or near, I won't forget old commitments. Elected as your deputy to the Assembly of Lower Canada during two Parliaments, if you've approved of my conduct and my principles, as I have reason to believe, I again offer my services in the new legislature. I offer this with the conviction that the time has arrived where one who sincerely loves his country should not withdraw before the sacrifices involved in a political life. Whatever unanimity to be found in the ordinary sentiments of the electors in your county, I look forward and hope to meet you in great numbers at the hustings. I'm counting on the well-known patriotism in a population of twenty-five thousand souls, from wherever they are summoned, to name but a single representative, while a little town of a few thousand electors will have the same privilege.

The events to come with regard to our country are of the most high importance. Canada is the land of our ancestors; it is our homeland, as it should be the adopted homeland of the different populations that come from the diverse parts of the globe to exploit its vast forests in the view to establish and permanently fix their homes and their interests. Like us, they should desire, above all else, the happiness and prosperity of Canada. It is a heritage that they should strive to transmit to their descendants on this young and hospitable land. Their children should be, like us, and above all, CANADIANS.

In America 2, the greatest benefit that the population enjoys is social equality; that reigns to the highest degree. If, in some old societies of another hemisphere, they seem to suffer for their happiness and their needs, it would also be true for the vigorous and strong populations of this new continent. In addition to social equality, we need political liberty. Without it, we will have no future; without it, our needs can not be satisfied; without it, we will not be able to achieve the vast potential of nature in America. With constant and directed efforts, with steadfastness and prudence towards this essential goal of our prosperity, we will obtain this political liberty. To prevents us from enjoying it, one would need to destroy the social equality which forms the distinctive character in the population of Upper Canada as well as in that of Lower Canada. For this social equality should necessarily bring political liberty. It is an irresistible need in the English colonies of North America. These values are stronger than laws, and nothing we know of nothing that will weaken them. There can exist in Canada no privileged caste above and beyond the mass of its inhabitants. One can create a title one day; the next you'll see the children dragging the parchment in the mud.

But what is the method of obtaining this political liberty, so essential to the peace and happiness of the colonies, and to the development of its vast resources? The method is the voluntary endorsement of the adoption of laws; it is the consent of the people to vote for taxes and to regulate their use; it is also the efficient participation in the actions of its government; it is the legitimate influence to move the cogwheels of administration, and it's effective constitutional control on the individuals given immediate purpose to affect this administration; it is, in one word, that which is the big question of the day, responsible government, such as we swear by and promise in the assembly of Upper Canada to obtain its consent to the principal of the union, and not that which is perhaps now being explained in certain quarters.

This principal in not a new theory. It is the primary engine of the English Constitution. Lord Durham, in recognizing the necessity of its application to the colonies in their local affairs, has touched upon the root of the problem and has recommended the only workable remedy. In the actual circumstances, the importance of this question is such that a candidate who has political principles attached to some prize cannot now hesitate to express his opinion on this subject. I am not part of the number of those who rest in a blind confidence with regard to the promises of the Governor General. Far from it. I believe that in practice he does not believe in this principal in good faith, and I think that more or less the clarity of his intentions will depend on the composition of the new Chamber of Assembly. Myself, I do not hesitate to say that I'm in favor of this English idea of responsible government. I see, in its operation, certain guarantees through which we can have a good and effective constitutional government. The colonists should have control over their own affairs. They should direct all their efforts toward this end; and to bring it about, we need the colonial administration to be formed and directed by and with the majority of representatives of the people, as is the only means "to administer the government of these provinces according to the desires and the interests of the people, and that they express by its Representative the just deference which is their due."

Another question just as important is that of the result of the union of the two provinces. It is an act of injustice and despotism, in that it is imposed without our consent, and in that it deprives Lower Canada of a number of its legitimate Representatives, in that it deprives us the usage of our language in the procedures of the Legislature, against the faith of treaties and the word of the Governor General; in that it makes us pay, without our consent, a debt which we have not contracted, in that it permits the Executive to illegally seize, under the name of civil lists, and without the vote of the people's Representatives, an enormous part of the country's revenue.

Will it follow that the Representatives of Lower Canada should advance, and without guarantee, the demand to repeal the union? No, they shouldn't. They should wait before adopting a measure whose immediate result may be to throw us, for an indefinite time, under the liberalticidal legislation of a Special Council, and leave us without any representation at all. It is general a large mistake on the part of the political parties of the colonies to think they have the sympathy of such or such an Imperial Minister. Whether the ministers in London are Tory, Whig, or Radical, it makes no difference to the political situation of the colonies. The past is there to convince us.

The Reformists, in both provinces, form an immense majority. It is these in Upper Canada, or at least their Representatives, who have assumed the responsibility of the act of Union, and of all its injuste and tyrannical dispositions through their detailed reports to the discretion of the Governor General. They do not know, nor could they approve the treatment this act does to the inhabitants of Lower Canada. If they have been wrong in their expectations, they should protest against these disposition which serves their political interests and ours at the caprices of the Executive. If they do not, they'll put the Reformists of Lower Canada in a false-position in this regard, and will instead expose themselves to the retarding the progress of reform for years to come. They, like us, will have to suffer internal divisions that a similar state of affairs will make inevitable. It is in the interests of the Reformists in both provinces to meet on legislative grounds, in a spirit of peace, union, friendship and brotherhood. Unity in action is necessary now more than ever. I have no doubt that, like us, the Reformists of Upper Canada feel the same need, and that in the first session of the Legislature, they'll give us non equivocal proof; that this, I hope, will be the gage of a confidence which is reciprocated and durable.

When the work of the regular and constitutional legislation is taken up again, another important question which is of an immediate interest for the inhabitants of Lower-Canada, will in all likelihood call attention to your deputies. I want to talk about the question of seigniorial rights. I share the sincere opinion that you have already expressed your attitudes on this in the sixth resolution of the assembly of your county on 11 June 1837, where you declared "in the view of assuring sooner or later the triumph of democratic principles, which can only found in a free and stable government on this new continent, we should employ all means in our power to equalize social conditions, taking away from government all hope in establishing a new aristocracy, however weak it may be, and that this assembly regards the most correct method to bring about this end the abolition of seigniorial rights, in accordance to such present possessors a just and reasonable compensation, and to establish a tenure entirely free where our values and our needs can be asserted highly and urgently."

Education is the first benefit that a government can give to a people. In the past there were schools that the Legislative Council closed. Public money would be better spent on their reopening than on bribing a police force which everyone repels and abhors. The establishment of our colleges everyday makes lies of these false and injurious assertions, preferred by the prejudiced and the impassioned, that the ignorance of Canadians comes from their pretentious indifference to education.

The development of our vast interior resources requires the

urgent opening of easy navigation between the sea to the lakes. The St. Lawrence is the natural canal for a large part of the West's products. If, to secure for ourselves this source of public and private riches, it requires the hand of man to come in and assist the means which nature offers us, we should not hesitate to give it a judicious and prudent cooperation.

These are my views on the general points of our political position. If they are yours, you'll prove it one day, when, in common with your reformist brothers, you'll be called to make a choice for a member to represent you in the United Legislature.

I have the honour to be

your devoted Servant,

L.H. Lafontaine

Montreal, 26 August 1840.

Notes

1. The word 'hustings' is italicized in the orginal since it is an English word that he used untranslated, and I left it italicized here simply for consistency.

2. Lafontaine here seems to mean `America` as in the continent, not the United States.