About Painting

The Old Paradigms: Are they still with us?

Dennis Young

In 1846, the 25-year-old French poet

Charles Baudelaire published a 72-page, pink-covered book reviewing the

Paris Salon. It was his second attempt at art criticism, and he was

feeling bold enough to commend very little of what he had seen. He paid

tribute to Delacroix and Ingres and a few others, but went as far as

declaring his hatred for the work of Horace Vernet. "We are in the

hospital of painting," he said. "We are probing its sores and its

sicknesses." And he identified these sicknesses as the "chic," the

"stereotype" and the "eclectic," concluding with his now familiar

assertion that the "great tradition" had been lost. It is the paradigms of

this tradition that, in the main, I propose to examine in what follows. I

shall also comment further on Baudelaire and his review.1

Let me emphasize at the start that the "paradigms" refer

to painting rather than to "art;" for painting existed long before the

wider concepts "art" and "artist" we use today -- concepts scarcely 300

years old. 2 Michelangelo, for instance, was known simply as a painter,

architect or sculptor, depending on what he was up to at the time, and

French texts still referred to him as an "artisan" in the 18th century --

there was no other term to use. When his younger friend, the painter and

self styled historian Giorgio Vasari, wrote his account of Michelangelo

and their predecessors, he therefore called the book The Lives of the

Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects, not The Lives of

the "Artists." Yet this latter is the title under which it is often

misleadingly translated. Similarly, the French Academy began as L'Acadmie

Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, and only became L'Acadmie des

Beaux-Arts in 1816. So my subject is painting, and, since the

significant paradigms of painting developed over a period of 500 years, I

shall move back and forth over the centuries to demonstrate their waxing

and waning. In the Middle Ages, it was commonly supposed that a painting

would be carried out "in the accustomed manner." Paintings were useful

objects, tendentious, didactic and ritualistic, and paid for according to

the amount of lapis lazuli or gold leaf specified in the contract, their

size, or the number of figures to be painted-- and their production was

regulated by the local guild, if indeed a painters' guild existed (if it

did not, painters were usually required to join the local saddle makers'

guild, since their occupation was frequently that of painting saddles). As

for aesthetics, Johan Huizinga, in his Waning of the Middle Ages,

and Umberto Eco, in his Art and Beauty in the Middle Ages, agree

that if Medieval writers experienced anything like what is today called

"aesthetic," they thought of it as communion with God and expressed it in

terms of amazement, rather than beauty, even though theories of beauty

figured in their writings. "Beauty," for them, was entangled with the

pleasures of interpreting symbols, with the cosmic proportions of the

universe, with Platonist "divine light," with "goodness" and moral

harmony, and sometimes even with size -- in contrast to the hedonistic

pleasure provided by richly embellished objects, which was recorded at

length by Abbot Suger at St. Denis (and denounced, predictably, by Bernard

of Clairvaux). It is not until Poussin, in the mid-17th century, that we

find a painter claiming that the aim of visual art is "delectation" -- a

statement that Erwin Panofsky regarded as revolutionary. 3 Eco concludes that

"the medieval philosophy of beauty was cut off from its artistic practice

as if by a sheet of glass." It would have been more correct for him to

have said "artisanal practice," for the reason I have given; but, that

apart, he is obviously correct --the artisans were too lowly for anyone to

want to get inside their heads, whether they were weavers, shoemakers,

jewellers or painters.

An occupation known as painting

The evolution from "painters" to "artists" was slow, and

for our purposes may be said to have begun in a manuscript book written

around 1400 by the Italian painter Cennino Cennini (none of whose actual

works have come down to us). This book he called "Il Libro dell

Arte"(correctly translated as "The Craftsman's Handbook"

because, to underline the point again, "arte," like the word "craft" in

Germanic languages, in those days meant "skill"). Cennini tells us that he

is writing about "an occupation known as painting." This occupation, he

says, "calls for imagination and skill of hand" -- and he goes on

about the "aim" of such skill, which turns out to be "to discover

things not seen, hiding themselves under the shadow of natural

objects." I interpret this as a statement about the noumenal, or spiritual

-- or, about ways of signifying these (I realize that "noumenal"

is a term invented by Kant, but Cennini's reference to "things hiding

themselves under the shadow of natural objects" is surely close). Equally

important, Cennini moots the word "imagination" for the first time since

antiquity, even though "imagination" by no means then implied that the

painter could depart from the traditional repertoire of images (given free

reign in that regard, imagination was seen as potentially diabolical and

likely to produce what today we might call "the return of the repressed").

The appeal for "imagination" was simply for more freedom in the

composition of the prescribed images, which Cennini connected to something

he called "individual style." He says that, having acquired the manner of

one master, the painter, if he has "any imagination at all," should be

able to proceed to a style individual to himself -- curiously

enough by "copying from nature." Exactly what he meant we can never know,

though it sounds like an embryonic version of what we mean today.

Nevertheless, set in their 14th century context, these prescient

assertions, evoking "imagination," "individual style," and "copying from

nature" (as opposed to using pattern books), create a nice paradox: the

painter is supposed to copy nature, but his aim in doing so is to signify

something supernatural or noumenal that nature obscures from everyday

vision. Cennini thus stands, Janus-like, at an end and a beginning -- for

the idea of copying from nature was to gather momentum so rapidly that

talk of "things not seen" was largely eclipsed within 30 years of his

book. True, it would return briefly at the end of the 1400s as

Neoplatonism, and again in the 19th century in the doctrines of

Swedenborg, Blavatsky and Steiner, to give us The Symbolist

Manifesto of 1886, but for the best part of the 500 years following

Cennini, painters would work within the paradigm formed by his notions of

imagination, copying from nature, and individual style.

Cennini also promoted the opinion that painting deserved

better than its classification among the so-called "Mechanical Arts,"

where saddle-making was itself only a sub-section of armouring, and where

it was often painting's dismal fate to have to look up to both. And his

solution was ambitious -- he packaged his new theses as an appeal for

painting to be reclassified among the so-called Seven Liberal Arts of the

universities (by the side of rhetoric, dialectic and grammar and, above

all, geometry). Such a move would have stood to raise the social status of

painters nearer to that of poets, although it would not have found much

support among poets themselves (who were often wealthy amateurs) or among

the theologians and philosophers who had entrenched the medieval division

of labour in terms of a numerology laid down by their classical forebears.

As far as they were concerned, there was an absolute barrier between the

intelligentsia of the seven liberal arts, who worked with their heads and

communicated in Latin, and the rest of the world, including painters, who

worked with their hands and spoke and read, if they read at all, in the

vulgar tongue.

Perspective

However, the status of painters was to take a

significant jump due to something Cennini had not foreseen -- for within

20 years or so of Cennini's handbook, the architect Brunelleschi was to

announce the first unified method of monocular perspective. The fact that

unified perspective should have been rationalized by an architect has

never been adequately explained, for painters themselves had long

struggled unsuccessfully to achieve it. However that may be, by 1435 the

elements of perspective drawing had not only been invented but laid out

theoretically in a treatise by Leon Battista Alberti, in complete

opposition to Cennini's assertion that the role of painting was "to make

visible the invisible." The aim of painting now became the reproduction of

the visible. Thus, on the very first page of his treatise, Della

Pittura, "About Pictures," Alberti states specifically "The painter

has nothing to do with things that are not visible." And he adds, "a

picture is nothing other than a cross-section of a visual pyramid upon a

certain surface." Painters, he says, take a surface and "present the

forms of objects on this surface as if it were transparent glass."

This new paradigm of the canvas surface as "transparent" came not only

with a perspective formula for creating the illusion, but with much more.

For instance, Alberti took up Cennini's assertion that painters should

have the status of poets, and, going further, launched the idea of the

"learned painter" -- learned in geometry and perspective, but also in

classical mythology and the Christian stories.

In contrast to Cennini, Alberti wrote from a

philosophical point of view that may be called Aristotelian, or even

positivist, in its emphasis on observation and experiment -- and if we

look at the rejection, 450 years later, of his view that "painters have

nothing to do with things that are not visible," that rejection (by the

French Symbolists whom we have already noted), was accompanied,

predictably, by polemics against positivism and materialism --

and even for hierarchy, as opposed to democracy.

Perspective drawing, then as now, relied upon a fictive

monocular peephole, through which the painter was assumed to be regarding

the world as he built up an illusionist representation of it. So, to

experience the illusion perfectly, the viewer should really have stood at

a peephole with her eye in a position replicating the painter's. However,

painters took little regard of the fact that viewers might never be able

to place themselves at such a spot and that they would for this reason

actually receive a distorted, or "anamorphic," view of the representation.

In fact, this anamorphosis had been understood, and compensated for, prior

to Alberti, in the Gothic cathedrals, where sculptures to be seen from

below were often elongated. However, we have all had the experience in the

movies where our perception quickly compensates for the anamorphic

distortions that occur when we sit at the side of the screen, and it would

have been odd if the early perspectivists had not understood it too.

Indeed, by 1550, highly distorted anamorphic images began to proliferate

just for amusement -- and 200 years after Alberti the Baroque muralists

even solved the anamorphic problems presented by painting on the inside of

a dome. However, it is likely that no painting, however ambitious,

conforms to every last refinement of perspective theory -- which would

mean not only the precise positioning of the observer but also a specially

conceived concave surface to support the painting at a constant radius

from the eye.

Of course, there is no such thing as binocular

perspective (though Cézanne seems to have attempted a kind of binocular

painting with shimmering contours), and perspective was not really a

science, though it was often called such. Perspective was an invented

tool. Still, its raison d'ètre was, like that of science, to

provide ordered representations of the phenomenal world, and until the

invention of photography it remained, in this, supreme. Nor did the advent

of photography end its utility -- for it became something called

"engineering drawing" without which the design of the machinery of the

industrial age would have been impossible -- an ironic ending to what

began as a humanistic triumph of the intellect.

Correspondences

However, the Renaissance conquest of the phenomenal

world did not immediately eclipse the medieval concept of "things not

seen, hiding themselves under the shadow of natural objects," a concept

which gained new legitimacy on the formation in Florence, in 1457, of an

academy for the study of the manuscripts arriving there after the fall of

Constantinople. This academy expanded a notion from Plato, dear to various

medieval philosophers, that the final aim of human existence was a vision

of beauty and light -- a notion that evolved into a species of sun worship

that even seems to have been behind the theory of the heliocentric

universe proposed by Copernicus (one of the great paradigm shifts of all

time). Michelangelo attended this Neoplatonist academy from the age of 15,

and, like Botticelli, derived from it the inspiration for some of his more

bizarre imagery (as in the tomb of Giuliano de'Medici). Leonardo, in

contrast, defied the trend and effectively backed Alberti, insisting that

truths must be tested by the senses ("all else is clamour," he is supposed

to have said).

As the Catholic Church's Counter-Reformation began,

however, Neoplatonism waned for several centuries, until the Symbolists

resurrected it. For instance, Gauguin's adoption of Symbolism was

coincident with his encountering a circle of younger artists who claimed

to be reading Plotinus and the Cabala and adopting the cult of Mithras.

Hence the appearance of dreamscapes and of the Tau cross in his paintings

of that time. The circle also read fragments from the self-styled 18th

century mystic, Emmanuel Swedenborg, who had borrowed from Plotinus a

theory of "correspondences" which held that all things in the phenomenal

world have a corresponding echo in the spiritual. This convenient

discovery had been taken up by Baudelaire in an essay of 1855, and

elaborated in a poem by him, actually called "Correspondences," in 1857.

Indeed, Baudelaire was so intrigued by the ideas of Swedenborg that the

hero of his early novel Le Fanfarlo was cast as actually keeping

a copy of Swedenborg's writings by his bed; and Baudelaire's poem, whose

Swedenborgian first line states, "Nature is a temple -- with living

pillars," thus became an anthem for the symbolist movement. In the same

poem Baudelaire also confirmed his interest in synaesthesia (that colours

could be heard and sounds be seen as colours, and so on), something that

Kandinsky was later to claim he actually experienced (hence Kandinsky's

woodcuts called Klange: "Sound"). The poet Mallarmé, who

succeeded Baudelaire among the Paris intelligentsia, also espoused the

noumenal, which he thought could be achieved by, among other methods, what

he called "vagueness." Hence the vagueness of formal definition in

faux naïf paintings of that time by Vuillard, Bonnard and others,

and hence the later co-opting of Monet to the symbolist camp at the time

of his almost unreadable paintings of the façade of Rouen cathedral (a

complete turnaround from the earlier casting of him as a "positivist" with

the other impressionists). Ultimately, the theory of vagueness amounted to

offering a poem or a painting as an object open to a multitude of shifting

perceptions: an object that supposedly carried intuitions of the noumenal

by its very manner of being in the world. This idea still clings

to the arts, in spite of the critique from semiology which asserts that

what we really see or hear are the signifiers of a theory, and it

is surprising how many abstract painters have rationalized their work this

way: not only Kandinsky, Malevich and Mondrian, but also Rothko and Barnet

Newman, and, most recently, the American painter Brice Marden. Commenting

on this in the 1890s to his son Lucien, the aging socialist vigilante,

Camille Pissaro, saw it as "the bourgeoisie restoring superstition to the

people," while the great 20th century skeptic, Marcel Duchamp, one of the

few people of the past century who actually made a study of perspective,

began a monumental work, The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors,

Even, which displays astonishing perspective skills in order to

collapse the tension between noumenal and phenomenal in sardonic laughter.

As you may know, Duchamp then went on to invent a method of creating

stereoscopic illusions for persons with only monocular vision --

something that until then had been thought impossible.

Academy

The institutions within which the old paradigms evolved

were, of course, the academies. The first academy of visual arts came

about in Florence in 1563. It was a product of complex motives, but it

will suffice to say that it came in response to appeals by the aging

Michelangelo and his friend Vasari (who wrote the "Lives"), who together

persuaded the Medici family to do for painting, sculpture and architecture

what their earlier "Academy of Letters" had done for the Tuscan language.

The result was a drawing academy (the Academia del'Disegno) emphasizing

perspective, mathematics, geometry, optics, and the study of the human

frame. Indeed, the emphasis on geometry in the drawing academy was so

strong that one of the two chairs of mathematics in the University of Pisa

was transferred to Florence, and in 1610 Galileo himself moved there. This

was encouraging: painters and sculptors now met with practitioners of the

liberal arts on a more equal footing, and with the official sanction of

the state. Indeed the title of "academician," conferred on selected

painters from time to time, became a minor order of nobility. However, the

academies did not teach painting. You learnt to draw in the academies, but

to learn to paint you had to enrol in the studio of a painter, preferably

a member of the academy, very much as the medieval apprentice had been

indentured to a master painter of the painters' guild -- and your

experience there would have been similar. After all, the academicians

needed cheap labour too.

Silent Poetry

Needless to say, academic theory leaned on Alberti's

Della Pittura, since it is there that we first read that the aim

of painting should be to retell the history and myth found in biblical or

classical writings. Indeed, soon after Alberti, it was popular to quote

the Greek Simonides, who had decreed that painting should be seen as

"silent poetry" and poetry heard as "a speaking picture." Leonardo,

standing aside from his contemporaries, as usual, and actually attempting

to raise painting above poetry, made fun of this and called poetry

"painting for the blind." But the academies made it a doctrine, and

seeking other snippets from the past came upon an essay, The Art of

Poetry, by the Latin poet Horace, which produced the phrase "ut

pictura poesis" ("as painting, so poetry").4 They also adopted

Aristotle's Poetics, where, in his section on "the objects of imitation,"

Aristotle says that poets, like painters, imitate men in action

and make them better or worse than average -- a statement taken to mean

that the human body in action gave a picture of the human soul.

As these bits and pieces were distilled over the years,

they were assembled into a theory formalized around the time of the

Drawing Academy by Ludovico Dolce. This formalization of the paradigm

"ut pictura poesis" produced five restrictive precepts that were

to serve the academy for almost 300 years. The precepts concerned

"instruction and delight," "imitation of classical models," "invention,"

"decorum" and "expression," and I shall discuss them in that order.

The first restrictive precept, that of "instruction and

delight", came from both Horace and Aristotle -- it meant that the aim of

the chosen story (the "istoria", or "history painting," as it

came to be called), must be to instruct the viewer in noble and decorous

behaviour, though in a manner that would please the eye, as poetry pleased

the ear. This marriage of "instruction" and "delight" survived for 200

years, and began to falter only after the death of Louis XIV of France,

when "delight" was severed from the equation during the period of the

regency, to became an excuse for hedonistic and erotic indulgence, as

portrayed for instance in the works of Watteau, and later actually

realized in the paintings of Boucher (what the theorists of the rococo

period called "divertissement"). You can follow this hedonistic

element through revivals of the rococo, like that which produced Renoir's

Bathers, through Gauguin and art nouveau, and then

through Bonnard and Matisse -- the latter writing his own hedonist

manifesto in 1908. After World War II, the New York critic Clement

Greenberg actually appealed for a "bland Apollonian art" (a way of

characterizing Matisse's hedonism). It can be argued that to some extent

his appeal was successful, but the existentialist temper of the time

frowned upon it and painters were always averse to seeming "merely

decorative" (something Matisse managed to avoid).

However that may be, the didactic aspect of "instruction

and delight," though increasingly ignored, was not entirely discarded,

since a travesty of it remained in the state propaganda machine,

particularly in the form of portraits. Furthermore, aristocratic hedonism

was to provoke a bourgeois moralist reaction that produced the

sentimentality of Greuze and, eventually, a return to themes of Roman

republican virtue, in the work of Jacques-Louis David, which helped to

bring about the downfall of the aristocracy itself. And, of course, a

version of "instruction" continued through the 19th century, both for and

against the various regimes, producing Goya's attacks on corruption and

war, Courbet's "Realism," the journal Le Réaliste and, as the newspaper

industry flourished, a mountain of caricature dominated by Daumier. Later,

in Stalin's Soviet Union, Zhdanov transformed it into Socialist Realism,

and a variation is alive today in the tendentious works of Hans Haacke,

and text pieces by Les Levine, Barbara Kruger and others -- but not really

in painting.

The second restriction within "ut pictura

poesis," that on "imitation," followed from the "instruction" idea. It

was pointed out that, for instruction in ideal human nature, it

was no use looking to living people -- and the painter should therefore

look to classical sculptures. Hence the portrait painter's sitter would be

posed after an image from the antique and hence David's quotations from

such sources -- and hence also the practice of drawing from the antique in

art colleges that continued through much of the 20th century, where

students were to be found, drawing from casts of the antique, whose

instructors were ignorant of the high-minded reason for which the practice

had been initiated.

The third restriction was on "invention," which had

remained unchanged since Cennini declared that it could apply only to the

composition, not to the subject, of the painting. In other words,

Christian stories and classical myths were supposed to provide the themes

by which "instruction" in noble behaviour would take place, and painters

were not encouraged to provide themes of their own, unless they chose

inferior subjects. In fact the academies for this reason created an actual

hierarchy of subjects based on the antiquated "Great Chain of Being" --

antique stories, or "history paintings," coming at the top, along with

portraits of the monarch, then portraits of the nobility (often with poses

taken from classical sculpture); then animal paintings; then landscapes

(because trees were lower in the Great Chain than animals); then still

lifes; and finally "genre" or "low life" paintings not fit to be seen in a

palace. The ideological implications of this are obvious to us but were

not, of course, to the painters themselves, although, not surprisingly,

painters of prestige bridled under such restraints. For instance, when

Veronese was brought before a tribunal of the Inquisition in Venice, for

being over-inventive in his portrayal of The Last Supper, he not

only pleaded that painters had been granted the same license as poets,

but, when ordered nevertheless to alter the work, he avoided doing so by

changing its title to Christ in the House of Levi, a theme where

the same restraints did not apply! Thus was the way prepared for

Baudelaire, in his reviews, to actually give marks for "invention."

It is the fourth and fifth of these restrictions that

are the most interesting. The fourth, that of "decorum," forbade excesses,

exaggerations and repulsive scenes, and required that every gesture of

limb and drapery be appropriate to the purpose of the story portrayed.

Horace (the Latin theorist) had insisted on similar limits, though his

examples seem odd. For instance, he warned against joining a human head to

a horse's neck or spreading varicoloured plumage over the limbs of

animals. This almost sounds like a tract against 20th century surrealist

imagery (after all, the so-called "surrealist marvelous" was supposed to

come exactly from the "chance encounter" of such incompatible things).

However, although the concept of decorum had been tested from time to time

(think for instance of Carravagio painting St. Matthew with dirty feet),

its erosion was slow. According to Walter Benjamin, as late as 1830 de

Vigny's translation of Othello failed because it was unacceptable

for a handkerchief to figure in a tragedy! However, de Vigny was still

alive to see Baudelaire make his notorious and calculated break with

decorum by the publication in 1857 of his collected poems, Flowers of

Evil. Baudelaire's poem "Carrion" in that book already sounds like

something from Salvador Dali: "Flies swarmed over the putrid belly / From

which emerged black battalions / Of maggots, which flowed like a thick

liquid / Along those human rags...." The success de scandale of

Surrealism came from similar breaches of decorum. Indeed, without a

principle of decorum, scandale would be impossible -- just as,

with few taboos to break today, scandals have become an uphill task for

painters and poets alike.

Expression

The final precept in the doctrine of "ut pictura

poesis" concerned "expression." In its earliest form, this was a

matter of getting right the gestures and facial emotions in the painted

images, so that viewers might experience those emotions themselves through

an assumed "sympathetic" faculty (something that psychology has to some

degree confirmed -- pointing out that if you contort your face to

look sad you can actually feel sad). However, in

practice it is not so easy. Even Alberti's Della Pittura had come

with a discussion of the problems that arise in depicting emotions:

"Think," says Alberti, "how, if you try to paint a laughing face, it can

come out as a weeping face." The problem remained so pressing 200 years

later that the first president of the French Academy, Charles Le Brun,

attempted a so-called "Anatomy of the Passions," based on Descarte's

theories about the pineal gland, which aimed at communicating the emotions

directly. At first glance this book seems astonishing: "rage"

really seems to communicate rage. But then you find that so does "fear,"

and you begin to see why he needs labels! In fact, he had unwittingly

devised a code, with the book as its key -- and unmediated

communication was as far away as ever. It was still in dispute only 20

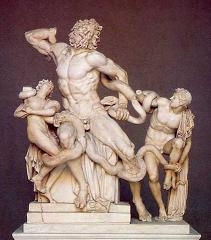

years ago, when the editor of the journal Modern Painters, the

late Peter Fuller, referring to the classical sculpture of Laocoön and his

sons being strangled by serpents, asked historian Grizelda Pollock, "How

do we know that Laocoön is supposed to be in pain?" and she replied,

"Because we have studied the mode of production prevailing in Greece at

the time, and the signifying practice to which it gave rise." "But," said

Fuller, "Laocoön is being strangled by a sea monster!" and her

response was, "Yes, but just by looking at the sculpture we have no way of

knowing he is not enjoying it." Fuller seemed to think that she had

thereby reduced her case to absurdity, but many think that she had not.

Psychology has shown that although visual forms may be "expressive," it

helps to have cues to tell us what they are expressive of (tears of joy,

or of sorrow?). I am reminded of an experience I had years ago when,

glancing at a muted television, I saw a crowd of obviously Arabic people

waving white scarves and dancing in what appeared to be a jubilant parade

-- then I turned up the sound and learnt that they were people from the

village where President Sadat of Egypt had been born, who were mourning

his assassination in a fashion customary to Egypt. I should have

remembered my Alberti.

Expressionism

However, the limiting of "expression" to the figures

portrayed was to die with the advent of van Gogh, who, as he acquired

the knack of the Impressionist brush stroke and encountered Gauguin's use

of colour, thought he could convey his own state of mind through

clashing colours, writhing contours and the ostensibly vigorous

application of the paint . Thus began the view that "expression" need no

longer be confined to the figures acting out their theatrical roles within

the picture, as decreed by "ut pictura poesis." Instead,

"expression" could be extended to the painter whose colours and marks

brought into existence the figures on the picture surface -- colours and

marks which by their lurid nature and agitated handling, in paintings by

Van Gogh, Munch or Nolde, could transmit the painter's own

exacerbated emotional states. However, it has to be said that claims to

communicate emotional states directly by colour and the handling

of paint are at least as problematic as Le Brun's efforts to do so with

physiognomy. It can be shown here too that suchclaims are mistaken and

that Expressionism is in fact a second order image repertoire,

relying, like all pictorial art, on external sources, contexts and cues --

such as the letters that Van Gogh wrote to his brother Théo, or the

journals in which Munch once wrote "Art is your heart's

blood."

It is no accident that the idea of

expressionism, as a movement, became fashionable just as the

Nordic/Teutonic countries of Europe were creating new national identities

(Germany was unified in 1871, the composer Sibelius completed his

Finlandia Suite in 1899 just prior to the independence of Finland, and

Munch's Norway separated from Sweden in 1907). In short, an important part

of their nationalist agenda was a disengagement from the classical

heritage of Greece and Rome that had been enshrined in "ut pictura

poesis." The Swedish novelist Pär Lagerkvist, writing "anguish,

anguish, is my heritage" as the epigraph to all his books, can scarcely be

confused with Rabelais. The cultural side of such nationalistic

differentiation, warranted perhaps by what we now call "seasonal affective

disorder," followed from theories of cultural relativism set afoot by the

German "Storm and Stress" movement of the late 18th century -- theories

that were later condensed into the snappy catch phrase, "race, milieu and

moment," by the French theorist Hippolyte Taine, professor of art history

and aesthetics at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris from 1863 (a

significant date, as we shall see). It is worth adding that Baudelaire,

who had discussed the contrast between Northern and Southern temperaments

in his Salon of 1846, proposed a formula that cited "l'èpoque, la

mode, la morale, la passion" as the determinants of style -- adding a

dandyish note to his compatriot's scientism.5

Grand Manner

As we have already said, the paradigm "ut pictura

poesis" determined the ranking of painters within the academy, where

the highest ranked painters were always the painters of the

istoria (the "history" painters) -- and not without

justification, since the skills involved in the design of a grand figure

composition were considerable, and the demand for such works in public

places, palaces and churches was heavy. "We measure a king by the grandeur

of his surroundings", said Jean-Baptiste Colbert, soon after the French

Academy was formed. This was a sentiment understood later by both Napoleon

I and Napoleon III, as well as by Louis XIV's successors, and dozens of

petty tyrants since. Colbert, who was both the Controller General of

Finance and Superintendent of Buildings under Louis XIV realized early in

the construction of the palace of Versailles that to fulfill his agenda of

aggrandisement it would be as well to have more academies -- so, besides

the Académie Royale de peinture et de sculpture, he created academies of

music, dance, architecture and science and even an academy of medals, as

well as a French Academy in Rome and the famous Rome Prize to go with it.

And, with Charles LeBrun, whom he appointed Director of the Académie, he

then determined a style suitable for his project -- the style known as

"The Grand Manner." Needless to say, the (now hilarious) subject set by

Colbert for the first Rome Prize competition turned out to be "Fame

Proclaiming the Marvels of the Reign of Louis XIV and Presenting his

Portrait to the Four Corners of the Globe," while six years later it was

"The King Granting Peace to Europe." It is interesting to note that the

Rome Prize competition was not to be abandoned until 1969, following the

French campus rebellions of 1968 -- when it was replaced by letters of

recommendation similar to those used for Canada Council grants today.

There was trouble in the French Academy from the start.

Le Brun's chief rival refused to join at all, and others joined mainly to

object to Le Brun and his promotion of Poussin. These were the followers

of Rubens -- led by a theorist called Roger de Piles who produced an

assessment of the great painters of history in order to give high marks to

Rubens and lower though not disrespectful marks to Le Brun and Poussin. Le

Brun, the leader of the Poussinistes, held views so rationalistic that he

had not only drawn up the physiognomy of the emotions that we have noted,

but had refused even to discuss colour, because it was not determined by

reason -- a somewhat extreme version of the attitude of formalist painters

down to the present day.

Inspired Genius

This lengthy quarrel, between the Poussinistes and the

Rubenistes, was to end in favour of the Rubenistes with the redefinition

of two ancient concepts -- those of "inspiration" and of "genius." The

Greeks had understood "inspiration" (being "breathed into" by your muse)

mainly as it affected actors and professional rhapsodes -- the reciters of

poetry. But Plato, with his distrust of poets, had laughed at it in his

dialogue Ion, and, since it was held that inspiration could not

be taught, the academy, like Plato, had given it a back seat.

However, with the redefinition of the word "genius," as the word we know

today, "inspiration" also got a lift.6 In classical times, that is to say, "genius" had

referred simply to the "spirit of the family," or the genetic makeup that

fathers handed on to children, and for the medievals it had even been

associated with the demonic because of its link to concupiscence. However,

as "inspiration" was rehabilitated and "genius" redefined, they were, as

we shall see, not only to encourage the more painterly, sketch-like

approach of the Rubenistes', but were to undermine the notion that

rigorous training was necessary to become a painter. They were also to

encourage the hyperbole of Shelley, who had actually translated Plato's

Ion yet in whose essay "The Defence of Poetry," we find the claim

that poets (and, by implication, painters) are "the unacknowledged

legislators of the world" who, like the ancient seers, are able to read

"the shadows which futurity castsupon the present" -- a notion amplified

from Aristotle's identification of poets as melancholics, to cast them as

pondering the human predicament from a lofty mountain top, disdainful of

the world below. This theme was also available from the Latin poet Horace

who had coined "ut pictura poesis." Horace had dismissed the

common people with the phrase profanum vulgus -- an expression

that two thousand years later lay in wait for Shelley's contemporary

Delacroix to repeat in his journal.

Genius and Sketches

The paradigm that equated inspiration and genius

with the painters' sketches was less lugubrious and became

enormously influential. Its traces survive even today. It too was first

mooted in Vasari's Lives, where he observes, "Many

painters achieve in their first sketch a boldness as if guided by the

fires of inspiration while, in finishing, the boldness vanishes." But, in

this, Vasari was once again ahead of his time, and the idea only took off

during the 18th century mutation of the word "genius" that we have just

described. This occurred alongside the emergence of art criticism -- so

that an early critic, Denis Diderot, having been electrified by watching

the painter Greuze make sketches (and almost certainly recalling Vasari),

could write, "A sketch is the artist's work when he is full of inspiration

and ardour, before reflection has toned things down. It is the artist's

soul expressing itself on canvas." If the word "authenticity" had been

around in those days Diderot would no doubt have used it too. Diderot's

contemporary, the German art historian Winckelmann declared the same about

modeling in clay, saying, "Modeling in clay is to the sculptor what

drawing on paper is to the painter in the soft clay, the genius of the

sculptor is seen in its utmost purity and truth." Diderot, of course, had

been the principal editor of the great Enlightenment project, The

Encyclopaedia, where it is explained for everyone to see, that

"genius" and "enthusiasm" are innate -- that they are "natural" and

therefore cannot be taught, any more than "inspiration" could be taught in

classical times. Such thinking added fuel to the dying embers of the

quarrel between the Poussinists and Rubenistes -- the Rubenistes arguing

for the marks of "genius" inscribed during the sketch, or what the Academy

called the "generative," phase of the composition, while the Poussinistes

believed that the "generative" phase must be followed by an "executive"

phase in which the work would indeed be completed. Thus the quarrel

between the Poussinistes and the Rubenistes became transformed into a new

dispute, during the 19th century, between the so-called "sketchers" and

the "finishers". Delacroix's Death of Sardanapalus was not only

condemned for lack of decorum but also for his "failure" to distinguish a

painting from a sketch, -- though his critics were to moderate their

language later as the tide began to turn in favour of the "sketchers."

Sketch and Salon

The dispute was particularly exacerbated by the method

of examination for the Rome Prize.7 This required that a painted sketch be completed

on the first day of the competition and a tracing of it left with the

examiners -- the student being expected to research the project over the

next weeks and produce a "finished" painting that exactly matched the

sketch. Students thus spent time rehearsing the all important "generative"

or "sketch" phase of the process, at the expense of "finish." The chief

promoter of this method of examination was the painter Geurin,

significantly the teacher of both Géricault and Delacroix -- both in their

different ways Rubenistes. However that may be, the situation permitted

students with less and less training in "finish" to enter the competition,

and encouraged well-trained artists to entrench themselves against the

sketchers -- so that the conflict quickly embroiled the juries of the

Salon (the annual exhibition event of the Academy, was called the "Salon"

because it was at first located in the Salon Carré in the Louvre

Palace). From its very beginning, it had been important for a painter to

get work into the Salon. And from the beginning the juries had manifested

bias -- both political, and art-political. So much so that, after his

rejection in 1769, the painter Greuze was to boycott the Salon for the

rest of his life, and to prosper without it. The event caused such turmoil

that the French Revolutionaries declared an unjuried "Open" Salon in 1791,

which was followed in 1806 by a "Salon des Refusés" (an exhibition to show

the rejects). There was a show of rejectsin a dealer's gallery in 1827,

and during the 1848 Revolution, 5,000 works were shown in another "Open"

Salon -- all of them setting a precedent for the famous Salon des Refusés

of 1863.

The jury for the official Salon of 1863 was to reject

roughly 4,000 paintings, among which were works by Manet, Cézanne,

Jongkind, Bracquemond, Pissarro, Fantin-Latour, Legros and Whistler -- the

last three of whom, all admirers of Delacroix, were to found the first

explicitly avant-garde group of painters, the societé des trois

("We three, we shall be the front runners," wrote Legros to Whistler). The

protests that followed this massive rejection, were so vociferous that

they persuaded Napoleon III not only to decree that the refused paintings

should have a show of their own, but also to decree that instruction at

the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, with its insistence on "finish," had suppressed

the "creative genius" of students and that the Academy would therefore

lose control of the teaching there. The decree of 1863 may thus be said to

mark the triumph of the "sketchers." Not surprisingly, Ingres, who had

himself boycotted the Salon for the preceding 30 years, called the decree

"the destructive language of Romanticism which expects to know

everything without an effort to learn anything."

Opaque

Napoleon III, himself, might never have sponsored these

changes (the "sketchers" were not exactly Bonapartistes, and portraits of

Napoleon and his family were painted mostly by Winterhalter, an expert in

"finish"), but Napoleon was in the process of a liberalization of his

regime, partly as the result of a series of articles by the architect

Violet le Duc, who had pointed out that the British World's Fair of the

previous year had revealed the Brits ahead of France in numerous sectors

of the economy, and also in design. It is true that after Napoleon III was

deposed in 1871, the Academy regained control -- but things were never to

be the same. The "sketchiness" of the late works of the British landscape

painter Turner, advocated by John Ruskin, became popular in France, and

were to influence not only Monet (whose "sketchy" Impression:

Sunrise came eight years after the decree), but also Whistler, the

first painter to pour liquid paint onto canvas, and the first to appeal to

the public to look not through the painted surface, but

at it -- exactly reversing Alberti's "transparent glass"

metaphor of 400 years earlier, and stressing instead the "opacity" of the

canvas surface and the "foregrounding" of the medium. Whistler, as

you may know, was to sue the critic John Ruskin, over the question of

whether his paintings could be called "finished," and though he was

awarded only a penny in damages, he nevertheless did win his case, his

success confirming in law, as it were, the paradigm of the sketch

-- a paradigm where temperament alone, or even eccentricity, could be seen

as the sufficient basis on which to produce a painting, eventually

persuading even Emile Zola that art was simply "nature seen through a

temperament." It is worth adding that this "foregrounding of the medium"

was also vindicated by the Italian Giovanni Morelli who created from it

his influential theory of connoisseurship, by taking photos of the least

"finished" details in paintings, such as ears or fingernails, where he

theorized that an artist's personal calligraphy would show best. In this

way, from 1880 onwards, Morelli was actually able to reattribute a series

of old master works in galleries throughout Europe.

Silent Music

The mention of Whistler brings us to the paradigm of

music. During the 3,000 years when painting was regarded as mimetic it was

easy enough to claim its parallel with poetry, because according to the

ancients, they both "imitated" human action (Greek poetry not being

published in books, but in public forums where it was declaimed

theatrically by the reciter, or rhapsode -- he whom Plato had

mocked in Ion). Aristotle even discussed music as mimetic, though

he did not marry it to painting as he married poetry. Then, too, in a

quite other dimension we find that the Seven Liberal Arts of the classical

period placed music side by side with geometry -- a classification so firm

that 1,500 years later, on the Royal Portal of the cathedral at Chartres,

there is a depiction of Pythagoras himself holding a musical

instrument. And he appears again in Raphael's School of

Athens, working on the mathematics of musical intervals. This was

because the Pythagorians had investigated the relation of musical pitch to

the length of the monochord in single string instruments, and had thereby

bequeathed a musical substratum to all geometric proportions -- including

those of architecture and painting. Thus Poussin quoted Greek musical

parallels and Joshua Reynolds, the first President of the British Royal

Academy, held that "architecture applied itself directly to the

imagination, like music," because it came without the mediation of

subject matter (more problematic semiotics). And, just prior to

Reynolds, there was a chapter in Charles Avison's Essay on Musical

Expression, of 1771, that affirmed the parallel of music and

painting not only by expounding on the Pythagorian references to

geometrical proportion, but also by adding a concept of "expressiveness"

which, according to Avison, had the power of "exciting the most agreeable

passions of the soul."

The heavy duty philosophers of the following century

were to identify music with Kant's noumenon -- as "the thing in itself,"

where all else was "merely appearance." Music, according to Schopenhauer,

represented the "will" (or life-force) directly; and Schiller

asserted that "The plastic arts at their most perfect must become music,

and move us by the immediacy of their sensuous presence." The

key, as Reynolds had said, lay in music's "immediacy," something that

painting lacked because its subject matter (its "iconicity" or "mimesis")

supposedly got in the way. Nevertheless, in 1834 the critic Gustave

Planche, writing on Delacroix's highly mimetic Women of Algiers,

was to see in that work "the art of painting itself, reduced to its own

resources without the aid of a subject"! It is significant that

among Delacroix's friends were the great musical virtuosi Paganini and

Chopin, and that Delacroix had painted sketchy portraits of both, naming

music as the source of his deepest artistic experience. Thus Delacroix

could write in his journal of "an arrangement of colours, lights and

shadows...that is called the music of the picture," and add, "before

knowing what the painting represents you can be caught by this

musical harmony." In his "Salon of 1844," the critic Théophile

Thoré took up the same theme in reviewing Delacroix's work, asking, "What

is the dominant note in the harmony of the picture?" and replying,

"Velasquez would have said, 'I am in the silver-grey tones,' and

Delacroix, 'My symphony begins in purple major and continues in green

minor'." Similarly, Baudelaire, an admirer of Delacroix, as we saw

earlier, wrote in his Salon of 1846, "A good way to tell if a painting is

melodious or not is to look at it from a distance too great to understand

its subject. If it is melodious, it already has meaning." These references

all suggest that the paradigm of painting as silent poetry was

about to be replaced by the paradigm of painting as silent music

-- an absolutely radical change brought about as attention was drawn to

the colour and facture of the paint on the canvas surface, by the

quarrel between "sketchers" and "finishers" that we have just discussed.

In fact, the new paradigm was made explicit in 1859, in an article in the

Gazette des Beaux-Arts by the critic Louis Viardot, who coined

the phrase "ut pictura musica" to replace what he Whistler began

to call his paintings "symphonies," "nocturnes" and "arrangements," and

that in 1890 Seurat, in a now well-known letter to his friend Maurice

Beaubourg, outlined a quasi-scientific theory of how to create mood in

painting by the use of line and colour.

Abstract Language

However, it is the English essayist, Walter Pater, to

whom we turn for an ultimate definition, which we find in his 1877 essay

"The School of Giorgione." In this essay, Pater asserts that all art

"aspires to the condition of music" and even speaks of an "abstract

language" and of "abstract colour" (words then only beginning to gain

currency). However, it is significant that in this epoch-making statement

Pater speaks of the condition of music -- he is not suggesting

that paintings become music, since he insists that "each art has

its own peculiar and untranslatable sensuous charm - its own special

responsibilities to its material" -- and he adds that the function of

criticism is to "estimate the degree to which a given work fulfils that

responsibility." Seventy five years later, the New York critic Clement

Greenberg was shamelessly to claim these insights as his own by rephrasing

them as the "area of proper competence of the medium," and demanding from

criticism the same measuring rod, without mentioning his source in

Pater.

The musical analogy was continued in the 20th century,

André Derain even taking a cue from Schoenberg's "emancipation of the

dissonance" of 1906 and announcing the same dissonant principle in the

painting of the Fauves. The broader paradigm spread to North America at

the time of World War I, and Greenberg used it somewhat obliquely during

World War II. I shall come back to that in a moment. Meantime it is worth

noting that the painter Jackson Pollock and the sculptor Anthony Caro,

endlessly discussed by Greenbergians, both invited the viewer to see their

work as "music," and in 1989 Gerhardt Richter, for whom Greenberg had

not the slightest affection, said the same. It seems they understood

music as a surrogate for the idea of the aesthetic object as "autotelic,"

as the thing that is an end in itself -- that has no purpose other than

its own existence. It was a way of avoiding further speech.

Medium Specificity

These notions of Pater's and Greenberg's may be said to

take up a discourse on "medium specificity" begun in an essay of 1766 by

Gotthold Ephraim Lessing. This essay, written at the very time that

Avison's musical analogy hit the streets, actually sets out to attack the

theory of "ut pictura poesis" by another route -- by criticizing

an interpretation of the sculpture we have already visited in our

discussion of the semiotics of expression, the sculpture of Laocoön and

his sons being strangled by serpents. The subject is found in a poem of

Virgil's, and Lessing points out that in the poem Laocoön lets out a cry

of anguish as he struggles, whereas in the sculpture he seems only to

sigh. Here, says Lessing, is an example of sculpture (and, pari

passu, of painting) not doing what poetry does -- the

explanation being that they exist in different media. In a diachronic art

like poetry, he says, you can have someone scream (because the

scream is only a fragment of time in the unfolding story), whereas a wide

screaming mouth in a synchronic art like sculpture remains fixed for all

time, looks hideous and does a disservice to the artist's aim. It may well

be said that while Lessing here successfully attacks "ut pictura

poesis," he is at the same time inadvertently defending its principle

of decorum in his assertion that a screaming mouth is beyond the limit.

Certainly Edward Munch saw it this way, because it was after reading a

new translation of Lessing that Munch set out to make a painting of a

"scream" in defiance of both arguments. Following the trend of the time

that we have already noted in Taine's "race, milieu and moment," Munch

evidently set out to create the signifier of the Nordic-Teutonic

expressive temperament, by theorizing that a scream can be

portrayed without a breach of decorum -- so long as the painter is

Norwegian!

The fact was, however, that what Lessing also wanted to

do was to start a debate on the semiotics of the different media by

contrasting the signs of which pictorial art is composed (what today we

call iconic, or "motivated" signs) and the words of which poetry is

composed (what we call "arbitrary" signs). In fact, in that way, Lessing's

essay makes an excellent introduction to the high cubism and papiers

collés of Picasso's and Braque's, where the two types of sign (the

iconic and the verbal) are welded together -- except that Lessing is a

century and a half too early.

The combination of Pater and Lessing, both of them

demanding respect for what Greenberg came to call the "proper competence"

of the medium, resulted in an essay of Greenberg's of 1940, significantly

entitled "Towards a Newer Laocoön," where he identifies progress towards

"the area of proper competence" as the task of Modernism itself, and in an

essay of around the same time, "Avantgarde and Kitsch," he draws on

semiotics to reinforce the point, taking on even Aristotle himself, over

Aristotle's view that music imitates the state of the soul "immediately."

Here, Greenberg astutely points out that Aristotle omitted to say that the

Greeks used music only to accompany verse and that the words of the

verse therefore actually mediated the meaning of the music. Greenberg

quotes Plato's earlier saying that "when there are no words it is always

difficult to recognize the meaning of the music or to see that any worthy

object is imitated by it," and he, Greenberg, goes on to say that as this

function was abandoned, as the words and music got separated, music was

forced to withdraw into itself to discover its own raison d'être -- as

has been the case with painting of the modern period. This withdrawal

of painting into itself, he says, has meant that the best artists become

"artists' artists" and are cut off from a public unwilling to become

initiated into their esoteric discourse -- with the result that the

survival of culture is threatened as the field is left to "kitsch." This,

with significant qualifications (for it is really too simplistic), is

still true, though it is not my intent to elaborate upon it here. It may

be added, however, that a species of "reductivist" painting was to follow

Greenberg's, though without his blessing, further restricting the idea of

"proper competence" to the processes by which the paint might be

applied -- a paradigm still functional in North America today.

Sublime

Some artists of whom Greenberg thought well,

particularly Barnett Newman, evoked an old paradigm that he did not

espouse. This was the "Sublime," a concept of the late 17th century that

had grown from an examination of ancient writings on rhetoric, especially

where rhetoric discussed the kind of elevated speech that produced

"marvelous" effects (early translations even contained the word

"marvelous" in their title). By the mid- 18th century, however, the notion

had been developed, particularly by Edmund Burke, into an aesthetic of the

terrifying applied to such events as shipwrecks, volcanic eruptions,

hurricanes, sharks and so forth, that over-awed the viewer by their

incalculable power, size or violence -- whether portrayed or actual. The

concept was made fun of by Pope, whose formalist aesthetics were opposed

to it,8 and

there are critics today who view it as reduced to the "ridiculous" by

advertising; but when one realizes that the hypnotic horror of the twin

towers exactly fits Burke's definition, the sublime bears further thought.

Like the notion of genius, it was a timely idea for the Romantic movement.

It gave permission for everything from "Gothic" novels to the nightmare

paintings of Fuseli and the molochism of Delacroix's Death of

Sardanapalus. At the end of the century, Emmanuel Kant found it

necessary to deal with the sublime, in his "Critique of Judgement," as an

issue apart from the beautiful (which for Kant was always experienced in

front of things bounded or contained, and never evoked by the vast and

unbounded). Kant's account is complex, but the fact that he tackled it at

all helped to perpetuate Burke's more available conception -- which in the

20th century became the "Futurist marvelous" when applied to the love of

danger, war, speed, electric tramcars and confrontations with the public,

and the "Surrealist marvelous" when applied to the indecorous results of

various chance procedures,9 becoming briefly respectable again in the New York of the

1940s, as the "abstract sublime," from which was eventually to come that

Canadian cause célèbre Barnett Newman's Voice of

Fire.

A variant of the sublime has been promoted by

Jean-François Lyotard as the essential motor of modern art -- though, on

examination, this turns out to be a version of the symbolists'

preoccupation with the noumenal -- an important but by no means sufficient

source of the modern. In proposing it, however, Lyotard had a motive --

which was to undermine what he calls the "grand narratives" of

historiography, like those produced by Marxian theory, and to substitute a

mixed bag of "less oppressive" little narratives; though it remains

unclear whether the two are mutually exclusive.

Modern Life

The "great tradition" that Baudelaire had proclaimed

lost, in his Salon of 1846, was essentially that of "ut pictura

poesis," or what he called there "the habitual, everyday idealization

of ancient life." Of course, by "lost," he meant, as much as anything,

"enfeebled;" and, though he had espoused the musical analogy that would

later feature in the shaping of abstraction, he suggested, as the remedy

for this enfeeblement, a dose of "modern life." Unfortunately, the only

exponent of modern life that he could find was the tepid, minor

painter-illustrator, Constantin Guys. You might have thought he would have

mentioned Gustave Courbet, just two years his senior, who by 1853 would

paint his portrait. But Courbet's heart was with the peasants of Ornans

with whom he had grown up, while that of Guys' was in the great faubourgs

of Baudelaire's Paris. In the end, the painter who would come to fill the

bill was Edouard Manet; but he was just 14 in 1846, with no idea that he

would be inspired by Baudelaire, on meeting him in 1859, to produce his

first mature work. This was a sketchy, "low life" painting called The

Absinthe Drinker, in seamless lineage with the "great tradition" but

viewed today as signaling the modern period -- the promised land that

Baudelaire, who died in 1867, was not to see.

Milling About?

So: are the old paradigms still with us? Obviously, some

survived, somewhat transformed, throughout the modern period and some did

not, while some were "partially eclipsed" (a phrase that Malevich in 1914

actually inscribed on a collage that displayed the Mona Lisa).

Their history may be seen as that of the rewriting of earlier achievements

in new terms -- terms which, once established, modified the template taken

for granted in the production of paintings, the template of what was

"given". It was this that Marcel Duchamp understood in 1912 when he began

the notes towards his so-called "Large Glass" with the phrase "Etant

Donnés" ("Being Given"). In Duchamp's eyes, the rate of paradigm

change had so accelerated as to make nonsense of the current definitions

of art, and to make this point the "Large Glass" was to become a

portmanteau into which he stuffed various old paradigms, however

disjunctive -- to disrupt once and for all the race for the new and

introduce a definition of art that would accommodate his "Readymades."

Once the implications of this were understood some 50 years later, it

became possible for philosophers like Arthur Danto to declare the

history of art to be over, and all the old paradigms thus made

available, if only through a rear-view mirror in a Looking-Glass world

ruled by irony. This seemed to be a cause of consternation among painters

on the panel "Issues in Abstract Painting," promoted by the Dalhousie

exhibition Hungry Eyes. The panel several times repeated the

view that words like "pluralism" and "post-historical" define the current

situation. They gloomily surmised that "forward-looking trends affiliating

several artists" were dead, and that, instead of "movements," what we had

was a "directionless milling about" that left no scope for originality,

except through nuanced reruns of abstraction from the past.

But the paradigm changes that were once called

"progress" can equally be seen as the creation of an expanding universe of

texts, all "nuanced reruns" from the past (there really isn't an

alternative to that): a view that still leaves viable the old formula

"instruction and delight," that does not limit the scope of painters to

raise our consciousness of some issue, private or public, with enough

freshness, subtlety or éclat to hold our attention; nor limit

intellectual enterprise, or forthright, hedonistic works -- though there,

of course, the painter, skating around obstacles of taste, between high

art and kitsch, will find thin ice. But that is every artist's lot,

remembering that kitsch (what Baudelaire complained about in 1846 without

that word to hand) need not be held at bay only by novelty, transgression

or scatology. And as for the "sublime," it begs for rehabilitation in the

face of current theories of the "abject"; for paintings also can be made,

like those of Anselm Kiefer's, that speak the rhetoric of tragedy, of

guilt and solitude and desolation, as no other medium can. We might all

ponder that.

Notes

1. A lecture given at Dalhousie

University Art Gallery in November 2002, during the city-wide

collaborative exhibition About Painting

2. See P.O.

Kristeller: "The Modern System of the Arts," part 1; Journal of the

History of Ideas, Oct. 1951

3. Erwin Panofsky:

Meaning in the Visual Arts (New York, 1955), p. 10. Panofsky

acknowledges that "delectatio" was understood by certain medieval

writers as the signifier of beauty, but he emphasizes that they never

claimed that it should be the end of painting.

4.See Rensselear

W. Lee: Ut Pictura Poesis: The Humanistic Theory of Painting (New

York, 1967).

5. What Baudelaire

actually said was, "Beauty is a divine gateau around which the period, its

fashion, its morale and its passion form a titillating crust to the

eternal element inside" (emphasis added). He was to elaborate exactly this

in a more complete account of his aesthetics, published in the newspaper

Le Figaro, in 1863 under the title "The Painter of Modern

Life."

6. Early

indications are in Vasari, who refers to Michelangelo's "divine talent"

(divinis ingegno) anachronistically changed to "inspired genius"

by George Bull in the 1965 Penguin Classics edition. Vasari also refers to

"tre nobilis arti" (three noble crafts), translated by Bull as

"three fine arts," a category not then available (see Kristeller, op.

cit.)

7.See Albert

Boime: The Academy and French Painting in the Nineteenth Century

(London, 1971).

8. Alexander Pope:

Peri Bathous, or the Art of Sinking in Poetry (1727).

9. In the 1930s,

the dissident Surrealist, Georges Bataille, attempted to subvert Breton's

"marvelous" by promoting what he called the "abject," the very obverse of

sublime. He developed this, ultimately scatological, program in largely

unpublished notes, translated by French psychoanalyst Julie Kristeva in

her Powers of Horror (1982). Scatalogical imagery, mostly

humourous, has always existed at the margin of the visual arts and the act

of painting as a barely sublimated version of infantile faecal daubing is a

commonplace of psychoanalysis. Bataille therefore aimed at what he called

desublimatory "transgressions," some of which showed up at the

time in works by Miro and Dali. Leaning on Kristeva's book, they showed up

again in the aesthetically deprived 1990s - as an act of desperation.